Winter Means Flood Season in Ohio

Are You Ready for Flood Season?

Wintertime in Ohio means flood season.

Take last February, for instance, when the Ohio River crested over 60 feet, making it the worst flood Cincinnati had seen in more than 20 years — since the deadly “Flood of 1997.”

As the calendar turned from February to March of that fateful year, a relentless 12-inch downpour over the southern and eastern parts of the state caused the Ohio River to crest at 64.5 feet. As a result, much of downtown Cincinnati remained under three to four feet of floodwater for several days.

As the calendar turned from February to March of that fateful year, a relentless 12-inch downpour over the southern and eastern parts of the state caused the Ohio River to crest at 64.5 feet. As a result, much of downtown Cincinnati remained under three to four feet of floodwater for several days.

The 1997 flood was the worst flooding event since 1948. And before it was all over, 24 Ohioans had lost their lives. Total damage to southern Ohio communities was estimated at more than $155 million.

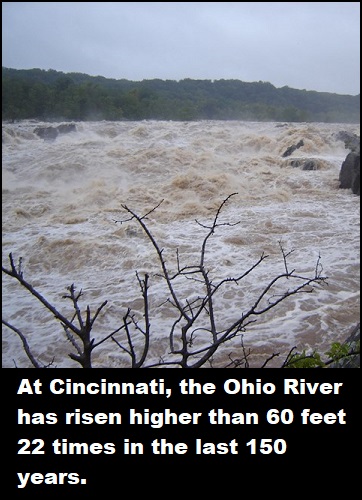

NWS Historical Flood Data

Altogether, the Ohio River at Cincinnati has risen higher than 60 feet 22 times since the National Weather Service began keeping records about 150 years ago.

Here are the agency’s top 10 historic crests for the Ohio River:

Here are the agency’s top 10 historic crests for the Ohio River:

(1) 80.00 ft on 01/26/1937

(2) 71.10 ft on 02/14/1884

(3) 69.90 ft on 04/01/1913

(4) 69.20 ft on 03/07/1945

(5) 66.30 ft on 02/15/1883

(6) 66.20 ft on 03/11/1964

(7) 65.20 ft on 01/21/1907

(8) 64.80 ft on 04/18/1948

(9) 64.70 ft on 03/05/1997

(10) 63.60 ft on 03/21/1933

And, as you can see, seven of these top 10 events occurred in winter.

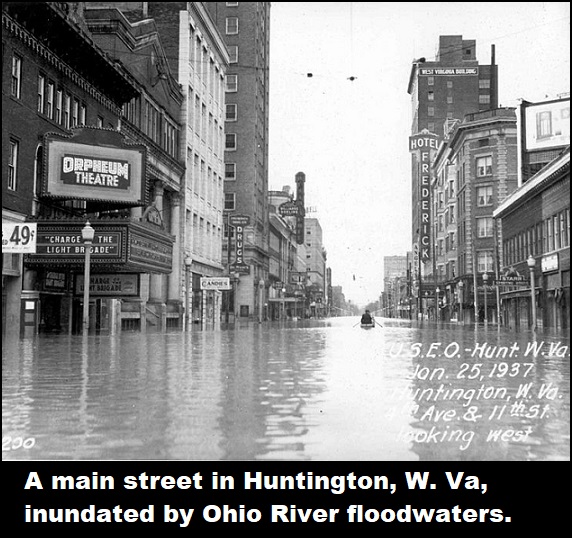

At the top of the list — and by far the worst flooding disaster ever to hit the state — was the Great Flood of 1937.

The Big One

In mid-January of 1937, tropical air masses collided with polar air masses over the Ohio River Valley and dropped an estimated 165 billion tons of water onto the Ohio and Mississippi River Basin. This was enough water to cover more than 200,000 square miles of land to a depth of 11-plus inches.

Between January 13 and January 25, six to 12 inches of rain fell over much of Ohio. Never before or since has such an enormous amount of rain fallen over such a large area of the state. (January 1937 remains the wettest month ever recorded in Cincinnati.)

Fifteen to 20 percent of the city of Cincinnati itself was water-covered, leaving thousands homeless. Parts of Cincinnati remained under water for 19 days. But much of the city outside of the flooded area was also paralyzed, due to lack of fresh water, electricity and heat. An estimated 100,000 residents of the Cincinnati tri-state area were permanently displaced by the flood.

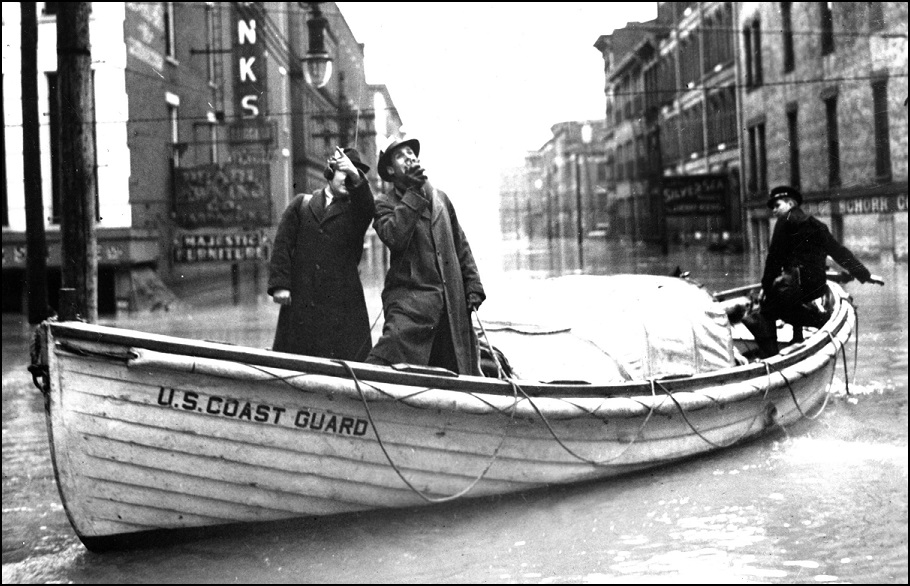

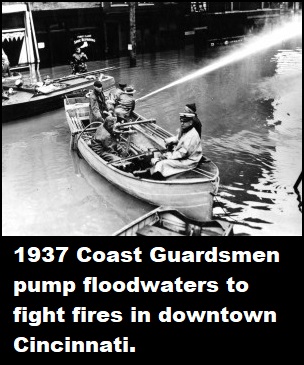

USCG to the Rescue

In response, and at the direction of President Franklin Roosevelt and his Secretary of the Treasury, the U.S. Coast Guard mounted the largest relief expedition in the history of the service.

Rescue operations extended from January 19 through March 11 and involved 351 boats of all types, as well as 12 aircraft, 10 of which were amphibious. The USCG also established an emergency radio network that included 244 stations.

It didn’t take long for rescuers to realize that the winter temperatures presented a dilemma. Floating ice in the northernmost parts of the river made navigation particularly hazardous. Rescue crafts sometimes capsized.

It didn’t take long for rescuers to realize that the winter temperatures presented a dilemma. Floating ice in the northernmost parts of the river made navigation particularly hazardous. Rescue crafts sometimes capsized.

Then — when it seemed that things could not get any worse — came “Black Sunday.” On January 24, the floodwaters in Cincinnati caused thousands of gallons of oil and gasoline to spill from storage tanks. The fuel ignited, resulting in the bizarre spectacle of burning buildings surrounded by water.

In order to extinguish the flames, the Coast Guard boats pumped the floodwaters into the already inundated buildings.

The Aftermath

By the time the floodwaters finally receded, the enormity of the devastation — stretching from Pittsburgh to Cairo, Ill. — was revealed. One million people were left homeless, 385 were dead and property losses reached $500 million (about $9 billion in 2018 dollars).

The scale of the 1937 flood was so unprecedented that civic and industrial groups lobbied national authorities to devise a comprehensive plan for flood control. The plan included the creation of more than 70 storage reservoirs to reduce Ohio River flood heights.

The Army Corps of Engineers finally completed the project in the early 1940s. Since then, the new facilities have drastically reduced flood damages along the Ohio. But, sadly, some communities never fully recovered from this epic disaster.

Sources:

WCPO Cincinnati

Cincinnati Enquirer

National Weather Service

Coast Guard Compass

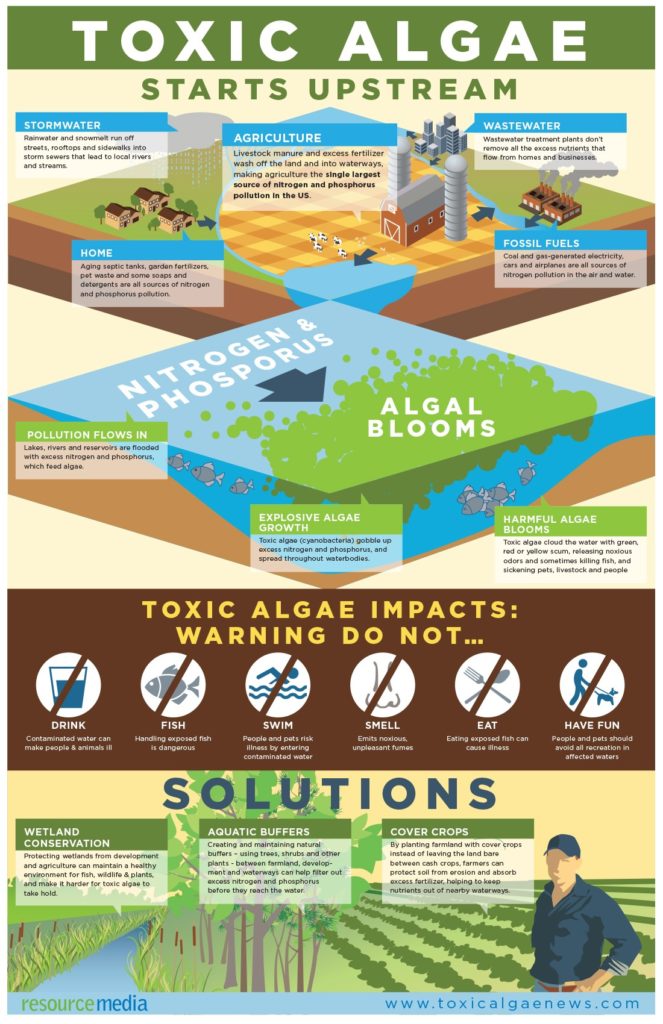

The Greater Cincinnati Water Works is well aware of the chemical levels in the

The Greater Cincinnati Water Works is well aware of the chemical levels in the

Most of the toxic compounds emanate from AK Steel’s Rockport, Indiana, plant, according to environmental website

Most of the toxic compounds emanate from AK Steel’s Rockport, Indiana, plant, according to environmental website

Because the

Because the