by Tom Barrett | Dec 5, 2018

Water for Energy for Water

Water and energy are inextricably linked.

It takes a significant amount of water to create energy. Likewise, it takes a significant amount of energy to extract, move and treat water.

U.S. power plants withdraw 143 billion gallons of fresh water every day. That’s more than the amount withdrawn for irrigation and three times as much as is used for public water supplies.

Water and Electricity

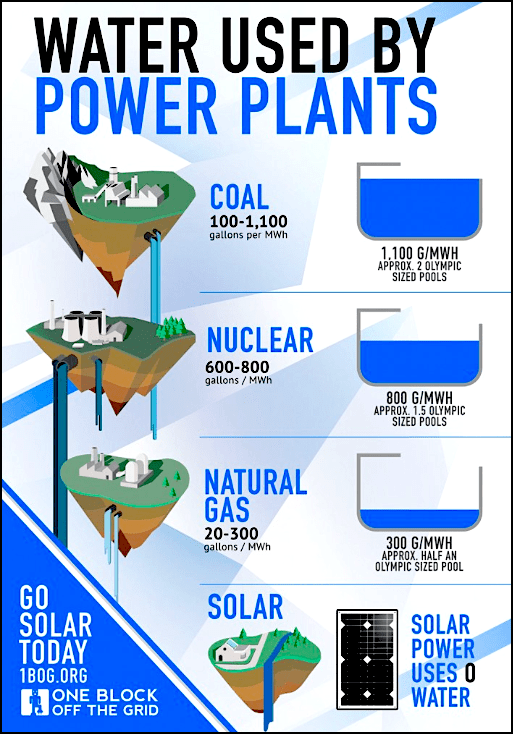

When we think of water and electricity, hydropower is usually the first thing that comes to mind. But power plants that use coal, oil, nuclear energy or natural gas are also water-dependent.

By burning coal or natural gas (or by maintaining a fission reaction), these power plants generate heat. The heat is then used to boil water, produce steam, and turn turbines. Much of the water used by these plants is needed to cool the steam they generate.

Withdrawal vs. Consumption

In order to better understand how much water is used by power plants, we must first define some terms.

Water “use” by power plants comes in two forms: withdrawal and consumption. Withdrawal refers to the amount of water a power plant extracts from a lake, river, aquifer, or other water source. Power plants that use “once-through cooling” technology withdraw large volumes of water a single time. They then discharge it directly to waste.

Water “use” by power plants comes in two forms: withdrawal and consumption. Withdrawal refers to the amount of water a power plant extracts from a lake, river, aquifer, or other water source. Power plants that use “once-through cooling” technology withdraw large volumes of water a single time. They then discharge it directly to waste.

Withdrawal is important for several reasons:

- Water intake systems can trap aquatic wildlife

- Water withdrawn for cooling (but not consumed) is returned to the environment heated, potentially harming wildlife

- Power plants that tap groundwater for cooling can deplete aquifers.

Consumption refers to the water that evaporates in the cooling process. Consumption reduces the amount of water available for other uses, such as sustaining ecosystems. Plants that use “recirculating cooling” technology tend to have lower rates of water withdrawal, but consume much more of that water through evaporation.

So How Much Water Do Power Plants Use?

A 2013 report published in Environmental Research Letters found that, in the year analyzed (2008), U.S. power plants:

- Withdrew some 50 trillion gallons of water

- Consumed 1.6 trillion gallons of that water

- Used freshwater (non-ocean) sources for 86 percent of those water withdrawals and 96 percent of the water they consumed.

This means that about 100 billion gallons of freshwater is withdrawn daily and several billion gallons consumed.

How does this compare with our other water needs, say, agriculture?

When it comes to withdrawals, power plants are number one. According to the most recent available data provided by U.S. Geological Survey, the power sector is responsible for more than 40 percent of freshwater withdrawals.

On the consumption side, agriculture is the biggest user. (Much of the water used to irrigate fields doesn’t make it back out.)

What Can Be Done?

As climate change continues to affect precipitation and temperature patterns across the country, water-dependent energy production could be inhibited.

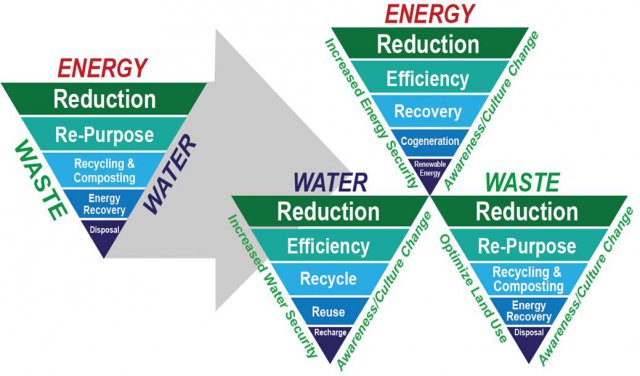

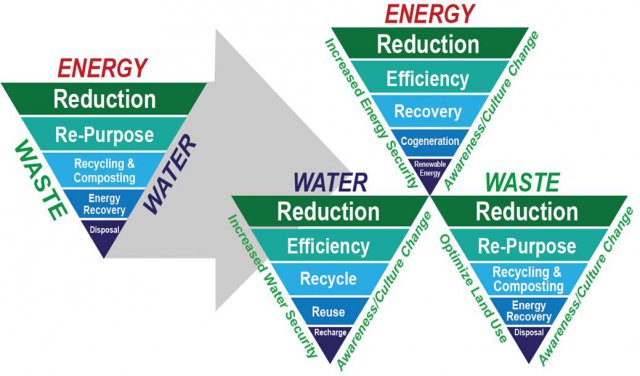

There are several ways we can address the water-related impacts of energy use:

There are several ways we can address the water-related impacts of energy use:

- Designing appliances, buildings, and vehicles to be more energy efficient. This is the simplest and most cost-effective solution. The less energy used, the less water required.

- Retrofitting old coal or nuclear power plants with more water-efficient cooling systems. According to scientists, this could potentially double water consumption, but could reduce water withdrawals to a mere fraction of current use.

- Encouraging (i.e., incentivizing) the expansion of renewable technologies (such as wind and solar energy) that require no water usage.

Sources:

Union of Concerned Scientists

National Conference of State Legislatures

U.S. Dept of Energy

by Tom Barrett | Feb 8, 2017

Ohio River Tops List of Most Polluted

The Ohio River is the most polluted body of water in the United States.

In fact, more than 24 million pounds of chemicals were dumped into the Ohio River by industries and businesses in 2013. That’s according to the most recent Toxic Release Inventory report produced by the Ohio River Valley Sanitation Commission.

How Bad Is It?

Although this sounds alarming, that figure is actually down from the high point of 33 million pounds in 2006. About 92% of the pollutants are nitrate compounds, commonly found in pesticides and fertilizers.

And, even more surprisingly, the river technically meets the human health standards for nitrates. So minimal changes are being made in their regulation.

But nitrates on the only problem the Ohio River has. Levels of mercury — a potent neurotoxin that impairs fetal brain development — in the Ohio River increased by more than 40% between 2007 and 2013, according to EPA data.

On the Waterfront

The Greater Cincinnati Water Works is well aware of the chemical levels in the Ohio River. Apparently, they have both carbon filtration and ultraviolet (UV) disinfection treatment systems in place to remove the toxins.

The Greater Cincinnati Water Works is well aware of the chemical levels in the Ohio River. Apparently, they have both carbon filtration and ultraviolet (UV) disinfection treatment systems in place to remove the toxins.

According to Jeff Swertfeger, Water Works’ Superintendent of Water Quality Management, “This facility is specially designed in order to remove the industrial-type contaminants like the gasolines, herbicides, pesticides, and things like that. If they get into the Ohio River and they get into the water, we can remove them here with our system.”

He added that the Water Works monitors chemical levels hundreds of times a day to ensure the drinking water is safe.

So Who’s to Blame?

Despite several clean-up initiatives and stricter regulation over the years, Ohio River industries still discharge more than double the amount of pollutants than the Mississippi River receives.

Most of the toxic compounds emanate from AK Steel’s Rockport, Indiana, plant, according to environmental website Outward On. But the plant shifts the blame to farm run-off from nitrogen-based fertilizers. Currently, the EPA does not require farm run-off to be reported in their Toxic Release Inventory.

Most of the toxic compounds emanate from AK Steel’s Rockport, Indiana, plant, according to environmental website Outward On. But the plant shifts the blame to farm run-off from nitrogen-based fertilizers. Currently, the EPA does not require farm run-off to be reported in their Toxic Release Inventory.

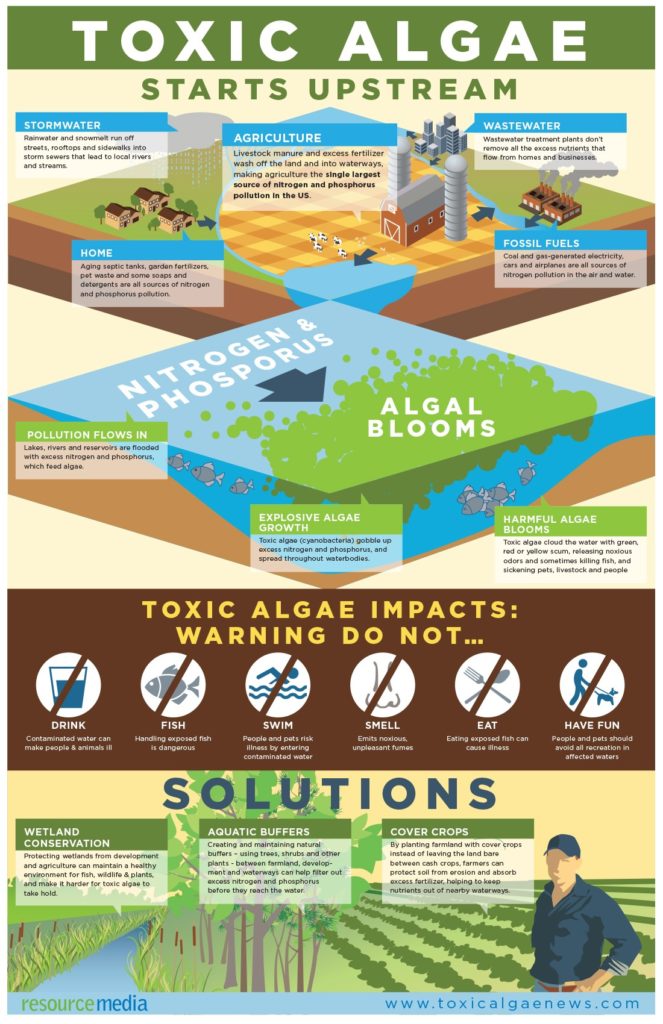

Science has shown that nitrates contribute to toxic algae blooms and oxygen-depleted dead zones. (Once such area in the Gulf of Mexico, for instance, is about the size of Connecticut.)

One Vision for Restoration

But Collin O’Mara, President and CEO of the National Wildlife Federation, is hoping to ignite a new vision for the region’s most vital natural resources.

“Twenty-five million people live in the Ohio River Valley Basin,” O’Mara said. “That’s almost a tenth of the country. And yet we’ve seen virtually no investment of federal resources in trying to clean up the legacy pollution. The Ohio is still the most polluted waterway in the entire country.”

That is not acceptable, according to O’Mara. “We’ve been working with some of the mayors and different advocacy groups in the region, trying to just begin talking about the Ohio River as a system and [develop] a vision for the entire watershed.”

Because the Ohio is considered a “working waterway,” it’s typically been treated as simply a support for larger industrial facilities. And while industrial jobs are important, O’Mara says, we cannot afford to degrade our waterways.

Because the Ohio is considered a “working waterway,” it’s typically been treated as simply a support for larger industrial facilities. And while industrial jobs are important, O’Mara says, we cannot afford to degrade our waterways.

“Right now across America, the outdoor economy is about a $646 billion economy. It employs more than six million people. And that puts it on par with many of the largest industries in the country. A lot of those jobs are water-dependent jobs related to fishing or swimming or outdoor activities. So one of the cases we’re trying to make is that it doesn’t have to be ‘either/or.’ The technologies exist now that we can actually have some industrial facilities and still not have to contaminate the waterway. ”

O’Mara added that “Given the political power that’s in the region between Pennsylvania, Ohio and Kentucky—I mean, you have some of the most important people in Washington that live along this watershed—there’s no reason why we can’t have significant investment go into the region.”

One thing is clear: Without significant change, the environmental future for the Ohio River is grim.

Hope Floats

But O’Mara is optimistic.

“If we can show progress in the Ohio River Valley…in a place that has a lot of legacy pollution…we can make it work anywhere.”

Until then, lest we forget what crystal clear water actually looks like:

Sources:

WLWT Cincinnati

Outwardon.com

WESA.fm

Environmental Law & Policy Center

Water “use” by power plants comes in two forms: withdrawal and consumption. Withdrawal refers to the amount of water a power plant extracts from a lake, river, aquifer, or other water source. Power plants that use “once-through cooling” technology withdraw large volumes of water a single time. They then discharge it directly to waste.

Water “use” by power plants comes in two forms: withdrawal and consumption. Withdrawal refers to the amount of water a power plant extracts from a lake, river, aquifer, or other water source. Power plants that use “once-through cooling” technology withdraw large volumes of water a single time. They then discharge it directly to waste.

There are several ways we can address the water-related impacts of energy use:

There are several ways we can address the water-related impacts of energy use:

The Greater Cincinnati Water Works is well aware of the chemical levels in the

The Greater Cincinnati Water Works is well aware of the chemical levels in the

Most of the toxic compounds emanate from AK Steel’s Rockport, Indiana, plant, according to environmental website

Most of the toxic compounds emanate from AK Steel’s Rockport, Indiana, plant, according to environmental website

Because the

Because the