by Tom Barrett | May 6, 2020

Ohio Watersheds Are Crucial to

Its Sustainability

We all live in a watershed.

Residential areas, farms, forests, small towns, big cities …They’re all part of a massive watershed network. Watersheds cross municipal, county, state and even international borders.

Pixabay Image

They come in all shapes and sizes, encompassing millions of square miles or just a few acres. And like creeks that drain into rivers, small watersheds are almost always part of a larger watershed.

For instance, Ohio’s 23 major watersheds consist of 254 principal streams and rivers. But they all drain into either Lake Erie or the Ohio River. (See “Ohio’s Two Primary Watersheds,” below.)

Our landscape and all its activities interconnect with streams, lakes and rivers through their watersheds. Naturally varying lake levels, water movement to and from groundwater, and amount of stream flow influences them as well. The health of our waterways is largely determined by these dynamics between the land and the water.

Ohio’s Two Primary Watersheds

In Ohio, rivers north of the Continental Divide flow to Lake Erie and the St. Lawrence Seaway. Rivers south of the Divide flow to the Ohio River and, eventually, the Gulf of Mexico.

Learn more about the Lake Erie watershed:

Learn more about the Ohio River Watershed:

Becoming Watershed Wise

Watersheds must be protected if they are to sustain life. When human activities alter the natural function of the watershed, residents can be adversely affected by frequent flooding and routine periods of drought.

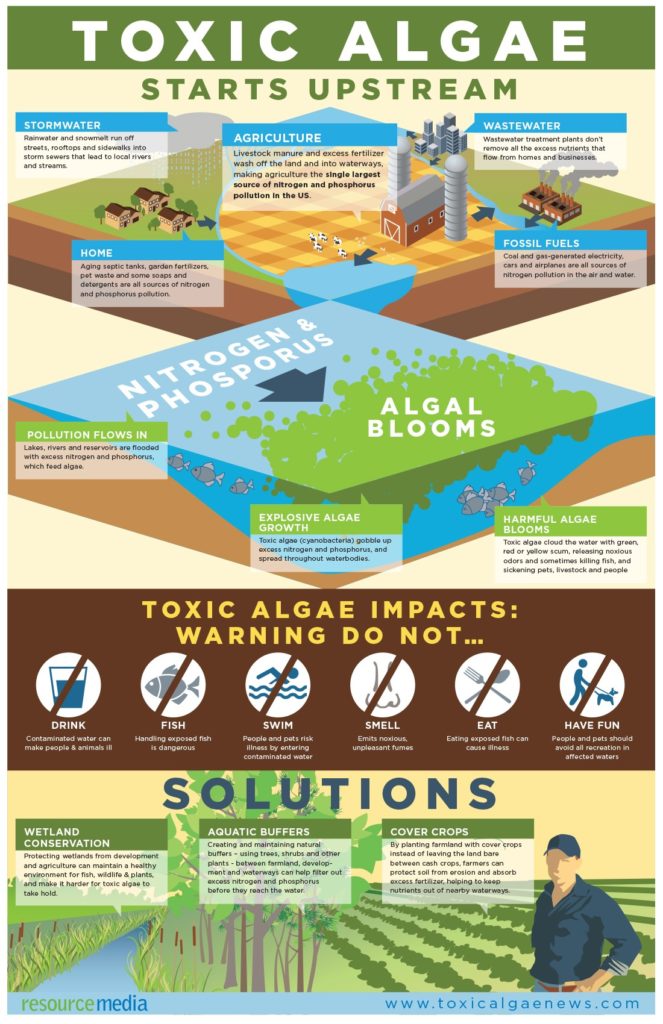

The three leading causes of polluted waterways are:

- Sediments

- Bacteria (such as E. coli), and

- Excess nutrients (such as nitrogen- and phosphate-based fertilizers).

Watershed-wise practices help create a balance and allow nature to work in our favor. When properly employed, residential landscapes can function as healthy mini-watersheds. The Green Gardens Group (G3) provides training and certification for its Watershed Approach to landscaping. This approach includes four key elements:

- Build Healthy Soil

- Capture Rainwater

- Select Native, Climate-Appropriate Plants

- Use Highly Efficient Irrigation

Smart irrigation technology (smart controllers, rain and soil-moisture sensors, and pressure regulators) is a key component of this approach and ensures optimal irrigation system performance.

Best Practices

As an irrigation and landscape professional, are you practicing watershed-wise principles, or are you contributing to the problem? Here are a few tips:

- Promote smart irrigation controllers and other technology with your customers, to ensure that runoff is reduced or even eliminated.

- Utilize matched precipitation rate (MPR) nozzles.

- Suggest that your customers create hydrozones (groups of plants with similar water needs) to conserve water.

- Offer your customers natural alternatives to nitrogen- or phosphate-based fertilizers? And suggest integrated pest management instead of pesticides.

- Make sure that roof runoff is directed onto a grassy area, not a sanitary or storm sewer system.

- Suggest porous surfaces for landscaping (such as flagstone, gravel or interlocking pavers), rather than impervious surfaces like concrete.

- Consider installing irrigation systems that draw from rainwater or gray water, whenever possible.

- Remind your customers that irrigation system management is critical! Systems must be actively and constantly managed in order to be watershed wise.

Take a Virtual Tour of

Ohio Watersheds

The Ohio Watershed Network offers a virtual tour of Ohio’s watersheds, beginning with the smallest streams in the watershed, the Headwaters.

From there, they move through the wider, slower-moving creeks and floodplains of the Middle Reaches. Then to the lakes, ponds and reservoirs, where sediments and many contaminants can collect.

The next stop is the precious Wetlands, with its large variety of plant and animal life. Finally, the last stop on the watershed tour is the Mighty River, where sediments, debris, or contaminants empty into the receiving waters.

We all affect the watershed, one way or another. Whether our individual influence is positive or negative is up to us.

Sources:

Featured Image: Pixabay

The Nature Conservancy

Green Gardens Group

WKYC

Ohio EPA

by Tom Barrett | Feb 8, 2017

Ohio River Tops List of Most Polluted

The Ohio River is the most polluted body of water in the United States.

In fact, more than 24 million pounds of chemicals were dumped into the Ohio River by industries and businesses in 2013. That’s according to the most recent Toxic Release Inventory report produced by the Ohio River Valley Sanitation Commission.

How Bad Is It?

Although this sounds alarming, that figure is actually down from the high point of 33 million pounds in 2006. About 92% of the pollutants are nitrate compounds, commonly found in pesticides and fertilizers.

And, even more surprisingly, the river technically meets the human health standards for nitrates. So minimal changes are being made in their regulation.

But nitrates on the only problem the Ohio River has. Levels of mercury — a potent neurotoxin that impairs fetal brain development — in the Ohio River increased by more than 40% between 2007 and 2013, according to EPA data.

On the Waterfront

The Greater Cincinnati Water Works is well aware of the chemical levels in the Ohio River. Apparently, they have both carbon filtration and ultraviolet (UV) disinfection treatment systems in place to remove the toxins.

The Greater Cincinnati Water Works is well aware of the chemical levels in the Ohio River. Apparently, they have both carbon filtration and ultraviolet (UV) disinfection treatment systems in place to remove the toxins.

According to Jeff Swertfeger, Water Works’ Superintendent of Water Quality Management, “This facility is specially designed in order to remove the industrial-type contaminants like the gasolines, herbicides, pesticides, and things like that. If they get into the Ohio River and they get into the water, we can remove them here with our system.”

He added that the Water Works monitors chemical levels hundreds of times a day to ensure the drinking water is safe.

So Who’s to Blame?

Despite several clean-up initiatives and stricter regulation over the years, Ohio River industries still discharge more than double the amount of pollutants than the Mississippi River receives.

Most of the toxic compounds emanate from AK Steel’s Rockport, Indiana, plant, according to environmental website Outward On. But the plant shifts the blame to farm run-off from nitrogen-based fertilizers. Currently, the EPA does not require farm run-off to be reported in their Toxic Release Inventory.

Most of the toxic compounds emanate from AK Steel’s Rockport, Indiana, plant, according to environmental website Outward On. But the plant shifts the blame to farm run-off from nitrogen-based fertilizers. Currently, the EPA does not require farm run-off to be reported in their Toxic Release Inventory.

Science has shown that nitrates contribute to toxic algae blooms and oxygen-depleted dead zones. (Once such area in the Gulf of Mexico, for instance, is about the size of Connecticut.)

One Vision for Restoration

But Collin O’Mara, President and CEO of the National Wildlife Federation, is hoping to ignite a new vision for the region’s most vital natural resources.

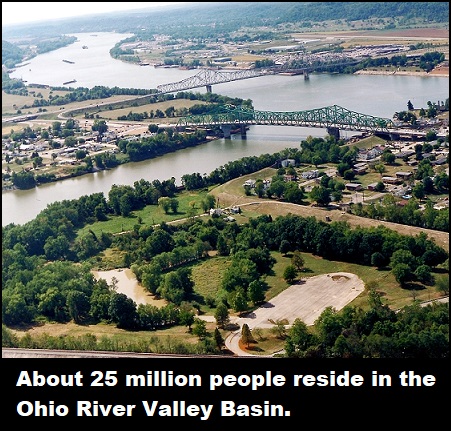

“Twenty-five million people live in the Ohio River Valley Basin,” O’Mara said. “That’s almost a tenth of the country. And yet we’ve seen virtually no investment of federal resources in trying to clean up the legacy pollution. The Ohio is still the most polluted waterway in the entire country.”

That is not acceptable, according to O’Mara. “We’ve been working with some of the mayors and different advocacy groups in the region, trying to just begin talking about the Ohio River as a system and [develop] a vision for the entire watershed.”

Because the Ohio is considered a “working waterway,” it’s typically been treated as simply a support for larger industrial facilities. And while industrial jobs are important, O’Mara says, we cannot afford to degrade our waterways.

Because the Ohio is considered a “working waterway,” it’s typically been treated as simply a support for larger industrial facilities. And while industrial jobs are important, O’Mara says, we cannot afford to degrade our waterways.

“Right now across America, the outdoor economy is about a $646 billion economy. It employs more than six million people. And that puts it on par with many of the largest industries in the country. A lot of those jobs are water-dependent jobs related to fishing or swimming or outdoor activities. So one of the cases we’re trying to make is that it doesn’t have to be ‘either/or.’ The technologies exist now that we can actually have some industrial facilities and still not have to contaminate the waterway. ”

O’Mara added that “Given the political power that’s in the region between Pennsylvania, Ohio and Kentucky—I mean, you have some of the most important people in Washington that live along this watershed—there’s no reason why we can’t have significant investment go into the region.”

One thing is clear: Without significant change, the environmental future for the Ohio River is grim.

Hope Floats

But O’Mara is optimistic.

“If we can show progress in the Ohio River Valley…in a place that has a lot of legacy pollution…we can make it work anywhere.”

Until then, lest we forget what crystal clear water actually looks like:

Sources:

WLWT Cincinnati

Outwardon.com

WESA.fm

Environmental Law & Policy Center

The Greater Cincinnati Water Works is well aware of the chemical levels in the

The Greater Cincinnati Water Works is well aware of the chemical levels in the

Most of the toxic compounds emanate from AK Steel’s Rockport, Indiana, plant, according to environmental website

Most of the toxic compounds emanate from AK Steel’s Rockport, Indiana, plant, according to environmental website

Because the

Because the